This concludes the series "SPY Week Famous Polish Spies". In the process of my research I had come across the names of many more Polish spies from the World War II era, but unfortunately due to lack of time I was unable to include them all in my special series. It would have been a monumental task far exceeding the confines of this blog.

Throughout the week, I have been awestruck by these dynamic and gifted people and their amazing stories. They must never be forgotten because their sacrifices were made not only for the freedom of Poland, but for the freedom of the world.

P.S.

the following was posted on January 14, 2018

In the process of reviewing this blog post, I noticed that the links to You Tube videos I embedded had all been broken. I had posted seven parts of a series called, "Subversion and control of Western Society which are instructional videos from Yuri Bezmenov, a KGB agent.. You may still find them on You Tube.

But instead of these videos I am posting just one, from Yuri Bezmenov. Even though it was made in the 1980s, I feel that the subject is more relevant than ever today. The title of this video, is aptly called, "How to Brainwash a Nation". Please share it with everyone you know. Our best defence is knowledge.

It is quite amazing how little we know know about propaganda, and even less able to recognize it when we see, read, or hear it. It's the most dangerous threat to our democratic nations, whether the propaganda is in our homeland, or from foreign sources.. I have already posted some blogs about propaganda, called World War II propaganda - War of Words, which focuses on Nazi and Soviet propaganda. Its worthwhile to read this as a starting point. I'm beginning to think I'll have to write much more on the subject!

Stay tuned!

Polish Greatness (Blog) is devoted to promoting Polish History, and gives tribute to the Polish Armed Forces past and present for their Courage, Honour and Sacrifices.

February 21, 2011

February 20, 2011

SPY WEEK Famous Polish Spies - Krystyna Skarbek

Krystyna Skarbek

Krystyna Skarbek (1 May 1915 – 15 June 1952) was a Polish Special Operations Executive (SOE

(1 May 1915 – 15 June 1952) was a Polish Special Operations Executive (SOE ) agent who became a legend in her own time for her daring exploits in intelligence and sabotage missions to Nazi-occupied Poland and France.

) agent who became a legend in her own time for her daring exploits in intelligence and sabotage missions to Nazi-occupied Poland and France.

She was a British agent just months before the SOE was founded in July 1940 and had been the longest serving of all British women agents during World War II. Skarbek was extremely resourceful and quite persuasive. Because of her influence the SOE began to recruit increasing numbers of women agents into the organization.

In 1941 she chose her began using the nom de guerre Christine Granville, which she ultimately legally adopted after the war. Skarbek was a friend of Ian Fleming, and is said to have been the inspiration for the charachters of Bond girls Tatiana Romanova and Vesper Lynd.

In 1941 she chose her began using the nom de guerre Christine Granville, which she ultimately legally adopted after the war. Skarbek was a friend of Ian Fleming, and is said to have been the inspiration for the charachters of Bond girls Tatiana Romanova and Vesper Lynd.

Krystyna Skarbek was born on an estate at Mlodzieszyn, 56 km (35 miles) west of Warsaw, to Count Jerzy Skarbek, a Roman Catholic and Stefania née Goldfeder, the daughter of a wealthy assimilated Jewish banker. It was a marriage of convenience which allowed Jerzy Skarbek the benefit of using Stefania`s dowry to pay his debts and continue his lavish life-style.

The Skarbeks were well connected with notable relations such as the composer Fryderyk Chopin, Chopin's godfather and prison reformer Fryderyk Skarbek, and American Union General Włodzimierz Krzyżanowski.

The couple's first child, Andrzej took after the mother's side of the family while, Krystyna, second born, took after her father. She shared his love for riding horses, which she sat astride, rather than side-saddle. During family visits to Zakopane in the mountains of southern Poland, she developed into an expert skier. From the very beginning, there was a complete rapport between father and daughter and her penchant for being a tomboy developed quite naturally.

Krystyna first met Andrzej Kowerski her childhood playmate, a her family stables, when his father met with her father the Count to discuss agricultural business. The 1920s financial crisis had left the family in dire financial straits in which they had to give up their country estate and move to Warsaw. In 1930, when Krystyna was just 22, her father died. The financial empire of the Goldfeder family had almost all but collapsed leaving barely sufficient money to support the widowed Countess Stefania.

Krystyna found work at a Fiat dealership but soon had to quit due to illness incurred as a result of the auto fumes. Initially, a doctor's diagnosis concluded that the shadows on her chest e-rays were that of tuberculosis, since her father had died of the disease. She received compensation from her employer's insurance company and followed the advice of her physician to spend as much time in the outdoors as possible. She spent a great deal of time hiking and skiing the Tatra Mountains in southern Poland.

During this time, Krystyna married a young businessman, Karol Getlich but the marriage ended amicably. They were incompatible. Subsequently, she was involved in a love affair, but it was nipped in the bud, as Karol's mother refused to allow him to marry a penniless divorcee.

One day while skiing at Zakopane, Krystyna lost control on the slopes and was saved in the nick of time by a giant of a man who stepped into her path and saved her. His name was Jerzy Giżycki - a brilliant, moody, irascible eccentric young man, who came from a wealthy family in Ukraine. At the age of fourteen, he had quarreled with his father, run away from home, and worked in the United States as a cowboy and gold prospector. Eventually he became an author and traveled the world in search of material for his books and articles. He had visited Africa and knew it well. It was his hope to one day return.

On 2 November 1938, Krystyna and Jerzy Giżycki married at the Evangelical Reformed Church in Warsaw. Shortly thereafter Jerzy accepted a diplomatic posting to Ethiopia, where he served as Poland’s consul general until September 1939, when Germany invaded Poland. Skarbek would later refer to Giżycki as having been "my Svengali for so many years that he would never believe that I could ever leave him for good."

LONDON

With the outbreak of World War II, the couple sailed for London, England, where Skarbek offered her services to the British Empire. At first the British authorities had little interest in considering her, but were eventually convinced by Skarbek's acquaintances, including that of journalist Frederick Augustus Voigt, who had previously introduced her to the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS). In 1940 Voigt was working as advsor for the British in the Department of Propaganda in Enemy Countries. After World War II, George Orwell described Voigt as a "neo-tory" who expounded on the need to maintain British imperial power as a necessary bulwark against communism and for the maintenance of international peace and political stability.

offered her services to the British Empire. At first the British authorities had little interest in considering her, but were eventually convinced by Skarbek's acquaintances, including that of journalist Frederick Augustus Voigt, who had previously introduced her to the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS). In 1940 Voigt was working as advsor for the British in the Department of Propaganda in Enemy Countries. After World War II, George Orwell described Voigt as a "neo-tory" who expounded on the need to maintain British imperial power as a necessary bulwark against communism and for the maintenance of international peace and political stability.

Skarbek travelled to Hungary and in December 1939 persuaded Polish Olympic skier Jan Marusarz, brother of Stanislaw Marusarz, to escort her across the snow-covered Tatra Mountains into Poland. Having arrived in Warsaw, she pleaded with her mother to leave Nazi-occupied Poland. Tragically, Stefania Skarbek refused to comply and died at the hands of the occupying Germans. In what was a cruel twist of fate, she perished in Warsaw's infamous Pawiak prison The prison had been designed in the mid-19th century by Krystyna Skarbek's great-great-uncle Fryderyk Florian Skarbek, a prison reformer and Frédéric Chopin's godfather, who had been tutored in French language by Chopin's father.

The prison had been designed in the mid-19th century by Krystyna Skarbek's great-great-uncle Fryderyk Florian Skarbek, a prison reformer and Frédéric Chopin's godfather, who had been tutored in French language by Chopin's father.

An incident in February 1940, illustrates the danger she faced while working as an undercover spy on home turf. At a Warsaw café, she was greeted by a female acquaintance who exclaimed: "Krystyna! Krystyna Skarbek! What are you doing here? We heard that you'd gone abroad!" Skarbek, with cool composure, denied that her name was Krystyna Skarbek, though the woman persisted that the resemblance was such that she could have sworn it was Krystyna Skarbek! After the woman had left, Skarbek remained some time at the cafe before leaving, so as not to arouse suspicion.

Krystyna Skarbek helped to organize a team of Polish couriers that transported intelligence reports from Warsaw to Budapest. Among them, was her cousin Ludwik Popiel who managed to smuggle out the unique Polish anti-tank rifle, model 35, with the stock and barrel sawed off for easier transport but it never saw wartime service with the Allies. Its designs and specifications had to be destroyed upon the outbreak of war and there was no time for reverse engineering. Captured stocks of the rifle were, however, used by the Germans and the Italians. For a period of time Skarbek, had the weapon concealed in her Budapest apartment.

In Hungary, Skarbek met long-lost childhood friend, Andrzej Kowerski, a Polish Army officer, who would later use the British nom de guerre "Andrew Kennedy". Skarbek met him again briefly before the war at Zakopane. Kowerski had lost part of his leg in a pre-war hunting accident, and was now exfiltrating Polish and other Allied military personnel and gathering intelligence.

In Hungary, Skarbek met long-lost childhood friend, Andrzej Kowerski, a Polish Army officer, who would later use the British nom de guerre "Andrew Kennedy". Skarbek met him again briefly before the war at Zakopane. Kowerski had lost part of his leg in a pre-war hunting accident, and was now exfiltrating Polish and other Allied military personnel and gathering intelligence.

Skarbek demonstrated her penchant for quick-thinking strategy. When she and Kowerski were arrested by the Gestapo in January 1941 she feigned symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis by biting her tongue until it bled. She won their release. Skarbek was related to the Hungarian Regent, Admiral Mikos Horthy, though a distant one at that. A cousin from the Lwów side of the family had married a relative of Horthy. The pair made good their escape from Hungary via the Balkans and Turkey.

Cairo

As soon as they arrived at SOE offices in Cairo, Egypt, they were stunned to discover that they were under suspicion.because of Skarbek's contacts with a Polish intelligence organization called the "Musketeers". The organization was formed in October 1939 by Stefan Witkowski, an engineer-inventor who would be assassinated in October 1941, whose identities have never been determined. Another source of suspicion was the ease with which she had obtained transit visas through French-mandated Syria and Lebanon from the pro-Vichy French consul in Istanbul, a concession offered only to German spies.

Suspicions also surrounded Kowerski and were addressed in London by General Colin Gubbins , head of the SOE (from September 1943). In a letter dated 17 June 1941 to Polish Commander-in-Chief and Premier Władysław Sikorski, he wrote the following:

, head of the SOE (from September 1943). In a letter dated 17 June 1941 to Polish Commander-in-Chief and Premier Władysław Sikorski, he wrote the following:

Eventually,Kowerski was able to clarify any misunderstandings with General Kopański following which he resumed intelligence work. Similarly, when Skarbek visited Polish military headquarters in her British Royal Air Force uniform, she was treated by the Polish military chiefs with the highest of respect.

Intelligence obtained by Skarbek through her connections with the Musketeers, had accurately predicted the invasion of the Soviet Union (June 22, 1941). Consequently, when Skarbek and Kowerski's services were dispensed with, Jerzy Gizycki took umbrage and abruptly resigned from his own career as British intelligence agent. (It was discovered only later that a number of Allied sources, including Ultra, also had similar advance information about Operation Barbarossa.)

Skarbek informed Jerzy, her husband that the man she loved was Kowerski. Giżycki left for London, eventually emigrating to Canada. Their divorce became official at the Polish consulate in Berlin on 1 August 1946.

Krystyna Skarbek was sidelined from mainstream action. The assistant to the head of F section, Vera Atkins, described Skarbek as a very brave woman, though very much a loner and a law unto herself.

France

By 1944 events had occurred that would lead to some of Skarbek's most famous of exploits. Due to her fluency in French, her services her offered to SOE teams in France, where she worked under the nom de guerre, "Madame Pauline". The offer was timely one - the SOE was encountering a shortage of trained operatives to meet the increased demands being placed on it in the run-up to the invasion of France. Though new operatives were already in training, the process took time to complete. The could not be posted throughout occupied Europe until they acquired the necessary physical and intellectual skills, otherwise their fate as well as that of other SOE colleagues and that of the French Resistance would be greatly compromised.

Skarbek's track record in courier work was exceptional during her missions in occupied Europe and required only a little "refresher" work and some guidance about working in France. There was one particular incident which required immediate attention: the replacement of SOE agent Cecily Lefort, a courier who was lost on a busy circuit whose mission it was to be the first to meet the proposed Allied landings. Skarbek was chosen to replace Lefort, who had been captured, tortured, and imprisoned by the Gestapo.

The SOE had set up several branches in France. Though most of the women in France reported to F Section in London, Skarbek's mission was launched from Algiers, the base of the AMF Section. This fact, combined with Skarbek's absence from the usual SOE training program, has been the source of mystery to many historians and researchers. The AMF Section was only set up in the wake of the Allied landings in North Africa, 'Operation Torch', comprising of staff from London's F Section and the MO4 from Cairo.

The functions of the AMF Section were three-fold: it was simpler and safer to run the resupply operations from Allied North Africa acroos German-occupied France, than from London; since the South of France would be liberated by separate Allied landings there ("Operation Dragoon"), SOE units in the area needed to be transferred to have links with those headquarters, not with forces for Normandy; the AMF Section tapped into the skills of the French in North Africa, who did not generally support Charles de Gaulle and who had been linked with opposition in the former "Unoccupied Zone".

After the two invasions, the distinctions became irrelevant; and almost all the SOE Sections in France would be united with the Maquis into the Forces Francaises de l'Interieur (FFI). (There was one exception: the EU/P Section, which was formed by Poles in France and remained part of the trans-European Polish Resistance movement, under Polish command.)

would be united with the Maquis into the Forces Francaises de l'Interieur (FFI). (There was one exception: the EU/P Section, which was formed by Poles in France and remained part of the trans-European Polish Resistance movement, under Polish command.)

On July 6, 1944, Skarbek, as "Pauline Armand", parachuted into southeastern France and became part of the "Jockey" network directed by a Belgian-British lapsed pacifist, Francis Cammaerts. She assisted Cammaerts by linking Italian partisans and French Maquis for joint operations against the Germans in the Alps and by inducing non-Germans, in particular Poles who had been conscripted in the German occupation forces to defect to the Allies.

On August 13, 1944, just two days before Operation Dragoon landings, Francis Cammaerts, another SOE operative,Xan Fielding who had been operating in Crete, as well as a French officer, Christian Sorensen, were arrested at a roadblock by the Gestapo. When Skarbek learned that they were to be executed, she managed to meet with Capt. Albert Schenck, an Alsatian, who was the liaison officer between the local French prefecture and the Gestapo. She introduced herself as a niece of British General Bernard Montgomery and threatened Schenck should any harm come to the prisoners. She reinforced her threat by offering two million francs for the men's release. Schenck in turn introduced her to a Gestapo officer, a Belgian named Max Waem.

landings, Francis Cammaerts, another SOE operative,Xan Fielding who had been operating in Crete, as well as a French officer, Christian Sorensen, were arrested at a roadblock by the Gestapo. When Skarbek learned that they were to be executed, she managed to meet with Capt. Albert Schenck, an Alsatian, who was the liaison officer between the local French prefecture and the Gestapo. She introduced herself as a niece of British General Bernard Montgomery and threatened Schenck should any harm come to the prisoners. She reinforced her threat by offering two million francs for the men's release. Schenck in turn introduced her to a Gestapo officer, a Belgian named Max Waem.

Skarbek's service in France restored her political reputation and greatly enhanced her military reputation. When the SOE teams returned from France some of the British women sought new missions in the Pacific War, however Skarbek, being Polish, was ideally suited to serve as a courier for missions to her homeland during the final missions of the SOE. As the Red Army advanced across Poland, the British government and Polish government-in-exile worked together to establish a network that would report on events in the People's Republic of Poland. Kowerski and Skarbek, fully reconciled with the Polish forces, were preparing to be dropped into Poland in early 1945. However, the mission, Operation Freston, was canceled because the first party to enter Poland were captured by the Red Army (they were released in February 1945).

All women SOE operatives were assigned military rank, with honorary commissions in either the Women's Transport Service - which was an autonomous, though elite part of the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) or the Women's Auxiliary Air Force. Skarbek appears to have been a member of both.

In preparation for service in France, Skarbek worked with the Women's Transport Service, but on her return had transferred to the Women's Auxiliary Air Force as an officer, a rank she held until the end of the war.

Skarbek was one of the few SOE female operatives to have been promoted beyond subaltern rank to that of Captain, or the Air Force equivalent, Flight Officer, the counterpart of the Flight Lieutenant rank for male officers. Skarbek, by the end of the war was Honorary Flight Officer, a title that of Pearl Witherington, the courier who had taken command of a group when the designated commander was captured, and Yvonne Cormeau, considered to be the most successful wireless operator.

Decorations

For her remarkable exploits at Digne, Skarbek was decorated with the George Medal. Years after the Digne incident, in London, she spoke about her experiences to another Pole, also a World War II veteran that, during her negotiations with the Gestapo, she was completely unaware of any danger to herself. Only after she and her comrades had escaped did she realize "What have I done! They could have shot me as well!"

In May 1947, she was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (O.B.E.) for her work in conjunction with the British authorities. This award is usually presented to officers about the rank of colonel, and a rank above the "standard" award of Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) given to other women of SOE.

In recognition of Skarbek's contribution to the liberation of France, the French government awarded her the Croix de Guerre.

After the war, Skarbek was left without financial reserves or a country to return to. Xan Fielding, whom she had saved at Digne, wrote in his 1954 book, Hide and Seek, and dedicated "To the memory of Christine Granville":

Death

Christine Granville met an untimely end at a Kensington Hotel on June 15, 1952 where she was stabbed to death by a man by the name of Dennis Muldowney, an obsessed merchant-marine steward and former colleague whose advances she had rejected. After being tried and convicted of her murder, Muldowney was hanged on the gallows at HMP Pentonville on 30 September 1952.

Krystyna Skarbek / Christine Granville was interred in St. Mary's Roman Catholic Cemetery at Kensal Green, in northwest London.

Following his death in 1988, the ashes of Skarbek's comrade-in-arms and partner, Andrzej Kowerski (aka Andrew Kennedy) were interred at the foot of her grave.

A Legend

Skarbek became a legend during her lifetime and after her death, has become forever after immortalized by popular culture. In Ian Flemings first James Bond novel, Casino Royale , the character Vesper Lynd is said to have been modeled after Skarbeck. According to William F. Nolan, Fleming also based Tatiana Romanova, in his 1957 novel From Russia, with Love

, the character Vesper Lynd is said to have been modeled after Skarbeck. According to William F. Nolan, Fleming also based Tatiana Romanova, in his 1957 novel From Russia, with Love , on Skarbek.

, on Skarbek.

Four decades later, in 1999, Polish writer Maria Nurowska published a novel, Milosnica (The Lover)—a fictional story about a female journalist's attempt to probe Skarbek's story.

(The Lover)—a fictional story about a female journalist's attempt to probe Skarbek's story.

A Polish TV series has been announced by Telewizja Polska (Polish Television) about Skarbek.

The Krakow Post report on February 5, 2009 that Agnieszka Holland will direct a big-budget film about Skarbek—Christine: War My Love.

Krystyna Skarbek

She was a British agent just months before the SOE was founded in July 1940 and had been the longest serving of all British women agents during World War II. Skarbek was extremely resourceful and quite persuasive. Because of her influence the SOE began to recruit increasing numbers of women agents into the organization.

In 1941 she chose her began using the nom de guerre Christine Granville, which she ultimately legally adopted after the war. Skarbek was a friend of Ian Fleming, and is said to have been the inspiration for the charachters of Bond girls Tatiana Romanova and Vesper Lynd.

In 1941 she chose her began using the nom de guerre Christine Granville, which she ultimately legally adopted after the war. Skarbek was a friend of Ian Fleming, and is said to have been the inspiration for the charachters of Bond girls Tatiana Romanova and Vesper Lynd.Krystyna Skarbek was born on an estate at Mlodzieszyn, 56 km (35 miles) west of Warsaw, to Count Jerzy Skarbek, a Roman Catholic and Stefania née Goldfeder, the daughter of a wealthy assimilated Jewish banker. It was a marriage of convenience which allowed Jerzy Skarbek the benefit of using Stefania`s dowry to pay his debts and continue his lavish life-style.

The Skarbeks were well connected with notable relations such as the composer Fryderyk Chopin, Chopin's godfather and prison reformer Fryderyk Skarbek, and American Union General Włodzimierz Krzyżanowski.

The couple's first child, Andrzej took after the mother's side of the family while, Krystyna, second born, took after her father. She shared his love for riding horses, which she sat astride, rather than side-saddle. During family visits to Zakopane in the mountains of southern Poland, she developed into an expert skier. From the very beginning, there was a complete rapport between father and daughter and her penchant for being a tomboy developed quite naturally.

Krystyna first met Andrzej Kowerski her childhood playmate, a her family stables, when his father met with her father the Count to discuss agricultural business. The 1920s financial crisis had left the family in dire financial straits in which they had to give up their country estate and move to Warsaw. In 1930, when Krystyna was just 22, her father died. The financial empire of the Goldfeder family had almost all but collapsed leaving barely sufficient money to support the widowed Countess Stefania.

Krystyna found work at a Fiat dealership but soon had to quit due to illness incurred as a result of the auto fumes. Initially, a doctor's diagnosis concluded that the shadows on her chest e-rays were that of tuberculosis, since her father had died of the disease. She received compensation from her employer's insurance company and followed the advice of her physician to spend as much time in the outdoors as possible. She spent a great deal of time hiking and skiing the Tatra Mountains in southern Poland.

During this time, Krystyna married a young businessman, Karol Getlich but the marriage ended amicably. They were incompatible. Subsequently, she was involved in a love affair, but it was nipped in the bud, as Karol's mother refused to allow him to marry a penniless divorcee.

One day while skiing at Zakopane, Krystyna lost control on the slopes and was saved in the nick of time by a giant of a man who stepped into her path and saved her. His name was Jerzy Giżycki - a brilliant, moody, irascible eccentric young man, who came from a wealthy family in Ukraine. At the age of fourteen, he had quarreled with his father, run away from home, and worked in the United States as a cowboy and gold prospector. Eventually he became an author and traveled the world in search of material for his books and articles. He had visited Africa and knew it well. It was his hope to one day return.

On 2 November 1938, Krystyna and Jerzy Giżycki married at the Evangelical Reformed Church in Warsaw. Shortly thereafter Jerzy accepted a diplomatic posting to Ethiopia, where he served as Poland’s consul general until September 1939, when Germany invaded Poland. Skarbek would later refer to Giżycki as having been "my Svengali for so many years that he would never believe that I could ever leave him for good."

LONDON

|

| Frederick Voigt |

With the outbreak of World War II, the couple sailed for London, England, where Skarbek

Skarbek travelled to Hungary and in December 1939 persuaded Polish Olympic skier Jan Marusarz, brother of Stanislaw Marusarz, to escort her across the snow-covered Tatra Mountains into Poland. Having arrived in Warsaw, she pleaded with her mother to leave Nazi-occupied Poland. Tragically, Stefania Skarbek refused to comply and died at the hands of the occupying Germans. In what was a cruel twist of fate, she perished in Warsaw's infamous Pawiak prison

|

| Pawiak Prison |

Krystyna Skarbek helped to organize a team of Polish couriers that transported intelligence reports from Warsaw to Budapest. Among them, was her cousin Ludwik Popiel who managed to smuggle out the unique Polish anti-tank rifle, model 35, with the stock and barrel sawed off for easier transport but it never saw wartime service with the Allies. Its designs and specifications had to be destroyed upon the outbreak of war and there was no time for reverse engineering. Captured stocks of the rifle were, however, used by the Germans and the Italians. For a period of time Skarbek, had the weapon concealed in her Budapest apartment.

In Hungary, Skarbek met long-lost childhood friend, Andrzej Kowerski, a Polish Army officer, who would later use the British nom de guerre "Andrew Kennedy". Skarbek met him again briefly before the war at Zakopane. Kowerski had lost part of his leg in a pre-war hunting accident, and was now exfiltrating Polish and other Allied military personnel and gathering intelligence.

In Hungary, Skarbek met long-lost childhood friend, Andrzej Kowerski, a Polish Army officer, who would later use the British nom de guerre "Andrew Kennedy". Skarbek met him again briefly before the war at Zakopane. Kowerski had lost part of his leg in a pre-war hunting accident, and was now exfiltrating Polish and other Allied military personnel and gathering intelligence.Skarbek demonstrated her penchant for quick-thinking strategy. When she and Kowerski were arrested by the Gestapo in January 1941 she feigned symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis by biting her tongue until it bled. She won their release. Skarbek was related to the Hungarian Regent, Admiral Mikos Horthy, though a distant one at that. A cousin from the Lwów side of the family had married a relative of Horthy. The pair made good their escape from Hungary via the Balkans and Turkey.

Cairo

As soon as they arrived at SOE offices in Cairo, Egypt, they were stunned to discover that they were under suspicion.because of Skarbek's contacts with a Polish intelligence organization called the "Musketeers". The organization was formed in October 1939 by Stefan Witkowski, an engineer-inventor who would be assassinated in October 1941, whose identities have never been determined. Another source of suspicion was the ease with which she had obtained transit visas through French-mandated Syria and Lebanon from the pro-Vichy French consul in Istanbul, a concession offered only to German spies.

Suspicions also surrounded Kowerski and were addressed in London by General Colin Gubbins

|

| General Gubbins |

Last year […] a Polish citizen named Kowerski was working with our officials in Budapest on Polish affairs. He is now in Palestine […]. I understand from Major [Peter] Wilkinson [of SOE] that General [Stanisław] Kopański [Kowerski's former commander in Poland] is doubtful about Kowerski's loyalty to the Polish cause [because] Kowerski has not reported to General Kopański for duty with the [Polish Independent Carpathian] Brigade. Major Wilkinson informs me that Kowerski had had instructions from our officials not to report to General Kopański, as he was engaged […] on work of a secret nature which necessitated his remaining apart. It seems therefore that Kowerski's loyalty has only been called into question because of these instructions.

Eventually,Kowerski was able to clarify any misunderstandings with General Kopański following which he resumed intelligence work. Similarly, when Skarbek visited Polish military headquarters in her British Royal Air Force uniform, she was treated by the Polish military chiefs with the highest of respect.

Intelligence obtained by Skarbek through her connections with the Musketeers, had accurately predicted the invasion of the Soviet Union (June 22, 1941). Consequently, when Skarbek and Kowerski's services were dispensed with, Jerzy Gizycki took umbrage and abruptly resigned from his own career as British intelligence agent. (It was discovered only later that a number of Allied sources, including Ultra, also had similar advance information about Operation Barbarossa.)

Skarbek informed Jerzy, her husband that the man she loved was Kowerski. Giżycki left for London, eventually emigrating to Canada. Their divorce became official at the Polish consulate in Berlin on 1 August 1946.

Krystyna Skarbek was sidelined from mainstream action. The assistant to the head of F section, Vera Atkins, described Skarbek as a very brave woman, though very much a loner and a law unto herself.

France

By 1944 events had occurred that would lead to some of Skarbek's most famous of exploits. Due to her fluency in French, her services her offered to SOE teams in France, where she worked under the nom de guerre, "Madame Pauline". The offer was timely one - the SOE was encountering a shortage of trained operatives to meet the increased demands being placed on it in the run-up to the invasion of France. Though new operatives were already in training, the process took time to complete. The could not be posted throughout occupied Europe until they acquired the necessary physical and intellectual skills, otherwise their fate as well as that of other SOE colleagues and that of the French Resistance would be greatly compromised.

|

| Cecily Lefort |

The SOE had set up several branches in France. Though most of the women in France reported to F Section in London, Skarbek's mission was launched from Algiers, the base of the AMF Section. This fact, combined with Skarbek's absence from the usual SOE training program, has been the source of mystery to many historians and researchers. The AMF Section was only set up in the wake of the Allied landings in North Africa, 'Operation Torch', comprising of staff from London's F Section and the MO4 from Cairo.

The functions of the AMF Section were three-fold: it was simpler and safer to run the resupply operations from Allied North Africa acroos German-occupied France, than from London; since the South of France would be liberated by separate Allied landings there ("Operation Dragoon"), SOE units in the area needed to be transferred to have links with those headquarters, not with forces for Normandy; the AMF Section tapped into the skills of the French in North Africa, who did not generally support Charles de Gaulle and who had been linked with opposition in the former "Unoccupied Zone".

After the two invasions, the distinctions became irrelevant; and almost all the SOE Sections in France

On July 6, 1944, Skarbek, as "Pauline Armand", parachuted into southeastern France and became part of the "Jockey" network directed by a Belgian-British lapsed pacifist, Francis Cammaerts. She assisted Cammaerts by linking Italian partisans and French Maquis for joint operations against the Germans in the Alps and by inducing non-Germans, in particular Poles who had been conscripted in the German occupation forces to defect to the Allies.

On August 13, 1944, just two days before Operation Dragoon

Cammaerts and the other two men were released. Capt. Schenck was advised to leave Digne. He did not and was subsequently murdered by a person or persons unknown. His wife kept the bribe money and, after the war, attempted to exchange it for new francs. She was arrested but released after the authorities investigated her story. She managed to exchange the money but received only a tiny portion of its value.For three hours Christine argued and bargained with him and, having turned the full force of her magnetic personality on him... told him that the Allies would be arriving at any moment and that she, a British parachutist, was in constant wireless contact with the British forces. To make her point, she produced some broken... useless W/T crystals.... 'If I were you,' said Christine, 'I should give careful thought to the proposition I have made you. As I told Capitaine Schenck, if anything should happen to my husband [as she falsely described Cammaerts] or to his friends, the reprisals would be swift and terrible, for I don't have to tell you that both you and the Capitaine have an infamous reputation among the locals.'

Increasingly alarmed by the thought of what might befall him when the Allies and the Resistance decided to avenge the many murders he had committed, Waem struck the butt end of his revolver on the table and said, 'If I do get them out of prison, what will you do to protect me?'

Skarbek's service in France restored her political reputation and greatly enhanced her military reputation. When the SOE teams returned from France some of the British women sought new missions in the Pacific War, however Skarbek, being Polish, was ideally suited to serve as a courier for missions to her homeland during the final missions of the SOE. As the Red Army advanced across Poland, the British government and Polish government-in-exile worked together to establish a network that would report on events in the People's Republic of Poland. Kowerski and Skarbek, fully reconciled with the Polish forces, were preparing to be dropped into Poland in early 1945. However, the mission, Operation Freston, was canceled because the first party to enter Poland were captured by the Red Army (they were released in February 1945).

All women SOE operatives were assigned military rank, with honorary commissions in either the Women's Transport Service - which was an autonomous, though elite part of the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) or the Women's Auxiliary Air Force. Skarbek appears to have been a member of both.

In preparation for service in France, Skarbek worked with the Women's Transport Service, but on her return had transferred to the Women's Auxiliary Air Force as an officer, a rank she held until the end of the war.

Skarbek was one of the few SOE female operatives to have been promoted beyond subaltern rank to that of Captain, or the Air Force equivalent, Flight Officer, the counterpart of the Flight Lieutenant rank for male officers. Skarbek, by the end of the war was Honorary Flight Officer, a title that of Pearl Witherington, the courier who had taken command of a group when the designated commander was captured, and Yvonne Cormeau, considered to be the most successful wireless operator.

Decorations

For her remarkable exploits at Digne, Skarbek was decorated with the George Medal. Years after the Digne incident, in London, she spoke about her experiences to another Pole, also a World War II veteran that, during her negotiations with the Gestapo, she was completely unaware of any danger to herself. Only after she and her comrades had escaped did she realize "What have I done! They could have shot me as well!"

In May 1947, she was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (O.B.E.) for her work in conjunction with the British authorities. This award is usually presented to officers about the rank of colonel, and a rank above the "standard" award of Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) given to other women of SOE.

In recognition of Skarbek's contribution to the liberation of France, the French government awarded her the Croix de Guerre.

After the war, Skarbek was left without financial reserves or a country to return to. Xan Fielding, whom she had saved at Digne, wrote in his 1954 book, Hide and Seek, and dedicated "To the memory of Christine Granville":

During the latter part of her life, she had met Ian Fleming, with whom she allegedly had a year-long affair,although there is no proof that this affair ever occurred. The man who made the allegation, Donald McCormick, relied on the word of a woman identified only by the name "Olga Bialoguski"; McCormick always refused to confirm her identify and did not include her in his list of acknowledgments.After the physical hardship and mental strain she had suffered for six years in our service, she needed, probably more than any other agent we had employed, security for life. […] Yet a few weeks after the armistice she was dismissed with a month's salary and left in Cairo to fend for herself ... [Alt]hough she was too proud to ask for any other assistance, she did apply for […] a British passport; for ever since the Anglo-American betrayal of her country at Yalta she had been virtually stateless. But the naturalization papers […] were delayed in the normal bureaucratic manner. Meanwhile, abandoning all hope of security, she deliberately embarked on a life of uncertain travel, as though anxious to reproduce in peace time the hazards she had known during the war; until, finally, in June 1952, in the lobby of a cheap London hotel, the menial existence to which she had been reduced by penury was ended by an assassin's knife.

Death

Christine Granville met an untimely end at a Kensington Hotel on June 15, 1952 where she was stabbed to death by a man by the name of Dennis Muldowney, an obsessed merchant-marine steward and former colleague whose advances she had rejected. After being tried and convicted of her murder, Muldowney was hanged on the gallows at HMP Pentonville on 30 September 1952.

Krystyna Skarbek / Christine Granville was interred in St. Mary's Roman Catholic Cemetery at Kensal Green, in northwest London.

Following his death in 1988, the ashes of Skarbek's comrade-in-arms and partner, Andrzej Kowerski (aka Andrew Kennedy) were interred at the foot of her grave.

A Legend

Skarbek became a legend during her lifetime and after her death, has become forever after immortalized by popular culture. In Ian Flemings first James Bond novel, Casino Royale

Four decades later, in 1999, Polish writer Maria Nurowska published a novel, Milosnica

A Polish TV series has been announced by Telewizja Polska (Polish Television) about Skarbek.

The Krakow Post report on February 5, 2009 that Agnieszka Holland will direct a big-budget film about Skarbek—Christine: War My Love.

|

| George Medal |

|

| Order of the British Empire |

|

| Croix de Guerre (France) |

Source: Wikipedia

Suggested Links:

Editors Note: FYI: The images of medals posted here may or may not be the exact version which was awarded to the recipient.There are several classes for each medal depending on various factors such as type of military (or civilian)service, rank of officer (or soldier), class of award, year in which it was awarded, etc. The lack of sufficient information on the web (or omission) has compounded the difficulty in selecting the correct class of medal. I apologize for any inaccuracies.

SPY WEEK Famous Polish Spies - Jerzy Sosnowski

Jerzy Sosnowski

Jerzy Sosnowski (December 3/4, 1896 - died 1942,1944 or 1945?) was a Polish spy in Weimar Germany (1926-1934) and a Major of the Second Department of the General Headquarters of the Polish Army (Dwójka). His code names were Georg von Nalecz-Sosnowski and Ritter von Nalecz. In the Soviet Union, he was known as Jurek Sosnowski, but other sources knew him by the name Stanislaw Sosnowski.

Sosnowski was born into an affluent family at the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His father was an engineer and owner of a construction company in Lwow. In August 1914 he joined the Polish 1st Legions Infantry Division and later transferred to the cavalry officers’ academy in Holitz. Upon graduating, he was sent to the Eastern Front and later completed a machine gunner course. In March 1918 he enrolled in an aviation course in Wiener Neustadt’s renowned Theresian Military Academy .

.

When Poland regained it's independence in 1918, Sosnowski enlisted in the newly created Polish Army. As a soldier of the 8th Uhlan Regiment of Prince Jozef Poniatowski, he fought with distinction and was promoted to the Rotmistrz.and became commander of a horse squadron of the 8th Regiment. Sosnowski was an excellent cavalry rider and participated in international tournaments in Paris and Berlin.

of Prince Jozef Poniatowski, he fought with distinction and was promoted to the Rotmistrz.and became commander of a horse squadron of the 8th Regiment. Sosnowski was an excellent cavalry rider and participated in international tournaments in Paris and Berlin.

Upon the advise of his friend, Captain Marian Chodacki, Sosnowski became a member of the Second Department of the General Headquarters, which was responsible for military intelligence as well as espionage activities. After completing a course he was sent to Berlin and became Director of the In-3 office of Polish intelligence.

When he arrived in Berlin, Sosnowski presented himself as Polish Baron Ritter von Nalecz expressing deep dislike for Jozef Pilsudski and seeking a close cooperation with Germany. He enacted a convincing role of a rabid anticommunist member of a secret anti-bolshevik military organization.

Young, dashing and handsome, the "Baron" quickly became popular among Berlin’s social and diplomatic circles. He was embroiled in a steamy love affair with an exotic night-club dancer by the name of Lea Niako, who ended up denouncing him to German counter-intelligence. He was arrested, and were it not for his diplomatic immunity, would have been sentenced to death. He was subsequently expelled from Germany.

He had an affair with Baroness Benita von Falkenhayn who was related to Erich von Falkenhayn, a former Chief of the General Staff of the German Imperial Army. In December 1926, he persuaded her to cooperate with Polish intelligence because of her many connections and detailed knowledge of the German General Staff. Soon afterwards, Sosnowski gained the services of Günther Rudloff, an officer of the Abwehr’s Berlin’s branch who agreed to cooperate - apparently because he owed a considerable amount of money to Sosnowski.

Sosnowski’s quick successes raised suspicions among officers of the Second Department of the General Headquarters in Warsaw. But his next achievements met with even greater success, that the Polish headquarters were convinced of his professionalism.

Among the agents working for the Polish spy included Irene von Jena and Renate von Natzmer, from Reichswehr’s headquarters (Reichswehrministerium). Sosnowski initially introduced himself as a British journalist by the name of Graves - as von Jena hated Poles, only later revealing his real identity. Other agents were Lotta von Lemmel and Isabelle von Tauscher as well as Falkenhayn and von Natzme, who became his lovers.

They all supplied Sosnowski with very useful information and documentation.

In 1929, with the help of Renate von Natzmer Sosnowski was able to obtain a copy of German war plans against Poland, entitled, "Organisation Kriegsspiel". He demanded 40 000 German marks for the document but his superiors in Warsaw refused to pay that much believing that the information he possessed was actually German disinformation. Sosnowski entered into a secret deal with von Natzmer. Ritter von Nalecz cut the price by half and finally after which he sent all documents to Warsaw for at no charge.The Polish authorities still declined to take advantage of these documents.

It is widely recognized that until 1934, the In-3 office headed by Sosnowski, and its base at the Polish Embassy in Berlin, were the best among foreign branches of Polish intelligence, its activities costing around 2 million zlotys, an expensive venture indeed.

By the fall of 1933 the Abwehr obtained details of the Polish network of agents from Lieutenant Jozef Gryf-Czajkowski, a double agent who had previously held Sosnowski’s post in Berlin and from Maria Krusek, a German actress and one of Sosnowski's lovers, both of whom betrayed Sosnowski in their allegiance to the Abwehr.

On February 27, 1934, Sosnowski was arrested by the Gestapo during a party in an apartment at 36 Lützowufer Street. Within days, many people were arrested including Benita von Falkenhayn, Renate von Natzmer, and Irene von Jena. Günther Rudloff avoided arrest claiming that he provided useful intelligence information to the Abwehr only because of his liaison with Sosnowski. Only later did the Nazis discover the truth about Rudloff's activities, and he was sentenced to death. He committed suicide on July 7, 1941.

On February 16, 1935 von Falkenhayn and von Natzmer were sentenced to death and later executed by at Plötzensee prison by beheading. Sosnowski and von Jean were sentenced to life imprisonment.

Sosnowski was bereaved at the deaths of his mistresses. He was quoted in Time Magazine, in the August 16, 1936 issue: "I am haunted by the deaths of those women. Until I was released in an exchange of prisoners I had seen no human face for 14 months. My food was lowered to me by guards from a trap door. The tragic deaths of those two - my former associates - haunt me night & day and I can only attempt to gain peace through prayer for their souls"

According to heresay Benita von Falkenhayn wanted to marry Sosnowski and obtain a Polish passport, thus saving her life, but Adolf Hitler thwarted her attempt.

Sosnowski was released in April 1936 when he was exchanged for three German spies caught in Poland. However, Polish headquarters instead accused Sosnowski with fraud and high treason and put him under house arrest. They had always been suspicious of Sosnowski and of his great successes.

His trial began on March 29, 1938 in the Military District Court in Warsaw where he was charged with treason and for collaborating with Germany. Sosnowski denied all charges but on June 17, 1939 he was found guilty and sentenced to 15 years imprisonment as well as a fine of 200 000 zlotys. He was about to appeal the decision but the outbreak of World War II made it impossible .

After this point in time, It is difficult to determine the fate of Sosnowski. According to one report he was evacuated east from prison in early September 1939 and shot by the prison guards on September 16 or 17, near Brzesc nad Bugiem or Jaremcze.

Another report claims that Sosnowski was shot but survived only to be captured later by the NKVD. He was arrested on November 2, 1939 by order of Pavel Sudoplatov and transported to the Lubyanka prison in Moscow. There, after "talks" with officers of Soviet intelligence he cooperated with them; allegedly working as an expert on Polish and German affairs, and participating in interrogations of General Mieczysław Boruta-Spiechowicz.

in Moscow. There, after "talks" with officers of Soviet intelligence he cooperated with them; allegedly working as an expert on Polish and German affairs, and participating in interrogations of General Mieczysław Boruta-Spiechowicz.

By the time the German-Soviet war began, Sosnowski was said to have become an NKVD

began, Sosnowski was said to have become an NKVD agent, and teaching at an espionage school in Saratov, where in 1943 he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

agent, and teaching at an espionage school in Saratov, where in 1943 he was promoted to the rank of colonel.

In the same year he allegedly was transferred to German-occupied Poland, where he cooperated with the communist People’s Army. It is rumoured that in September 1944 during the Warsaw Uprising , he ended up in Warsaw, where he probably died.

, he ended up in Warsaw, where he probably died.

Ivan Serov maintained that Sosnowski was executed by the Home Army in 1944, however, Pavel Sudoplatov claimed in 1958, that Sosnowski was executed in 1945 by order of Nikita Khrushchev. Some Russian sources claim that he died in 1942 in Saratov, during a hunger strike.

in 1944, however, Pavel Sudoplatov claimed in 1958, that Sosnowski was executed in 1945 by order of Nikita Khrushchev. Some Russian sources claim that he died in 1942 in Saratov, during a hunger strike.

Suggested Links:

"Love, Espionage and the Ax" (English, German, and Polish translations)

"Germany: Baroness Beheaded" Time Magazine, February 25, 1935

Jerzy Sosnowski (December 3/4, 1896 - died 1942,1944 or 1945?) was a Polish spy in Weimar Germany (1926-1934) and a Major of the Second Department of the General Headquarters of the Polish Army (Dwójka). His code names were Georg von Nalecz-Sosnowski and Ritter von Nalecz. In the Soviet Union, he was known as Jurek Sosnowski, but other sources knew him by the name Stanislaw Sosnowski.

Sosnowski was born into an affluent family at the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His father was an engineer and owner of a construction company in Lwow. In August 1914 he joined the Polish 1st Legions Infantry Division and later transferred to the cavalry officers’ academy in Holitz. Upon graduating, he was sent to the Eastern Front and later completed a machine gunner course. In March 1918 he enrolled in an aviation course in Wiener Neustadt’s renowned Theresian Military Academy

When Poland regained it's independence in 1918, Sosnowski enlisted in the newly created Polish Army. As a soldier of the 8th Uhlan Regiment

Upon the advise of his friend, Captain Marian Chodacki, Sosnowski became a member of the Second Department of the General Headquarters, which was responsible for military intelligence as well as espionage activities. After completing a course he was sent to Berlin and became Director of the In-3 office of Polish intelligence.

When he arrived in Berlin, Sosnowski presented himself as Polish Baron Ritter von Nalecz expressing deep dislike for Jozef Pilsudski and seeking a close cooperation with Germany. He enacted a convincing role of a rabid anticommunist member of a secret anti-bolshevik military organization.

Young, dashing and handsome, the "Baron" quickly became popular among Berlin’s social and diplomatic circles. He was embroiled in a steamy love affair with an exotic night-club dancer by the name of Lea Niako, who ended up denouncing him to German counter-intelligence. He was arrested, and were it not for his diplomatic immunity, would have been sentenced to death. He was subsequently expelled from Germany.

|

| Lea Niako |

| ||

| The Adlon Hotel and French Riviera were among the place of many lavish soirees attended by Sosnowski and his contacts. |

He had an affair with Baroness Benita von Falkenhayn who was related to Erich von Falkenhayn, a former Chief of the General Staff of the German Imperial Army. In December 1926, he persuaded her to cooperate with Polish intelligence because of her many connections and detailed knowledge of the German General Staff. Soon afterwards, Sosnowski gained the services of Günther Rudloff, an officer of the Abwehr’s Berlin’s branch who agreed to cooperate - apparently because he owed a considerable amount of money to Sosnowski.

|

| Benita von Falkenhayn |

Sosnowski’s quick successes raised suspicions among officers of the Second Department of the General Headquarters in Warsaw. But his next achievements met with even greater success, that the Polish headquarters were convinced of his professionalism.

|

| Erich von Falkenhayn |

Among the agents working for the Polish spy included Irene von Jena and Renate von Natzmer, from Reichswehr’s headquarters (Reichswehrministerium). Sosnowski initially introduced himself as a British journalist by the name of Graves - as von Jena hated Poles, only later revealing his real identity. Other agents were Lotta von Lemmel and Isabelle von Tauscher as well as Falkenhayn and von Natzme, who became his lovers.

They all supplied Sosnowski with very useful information and documentation.

In 1929, with the help of Renate von Natzmer Sosnowski was able to obtain a copy of German war plans against Poland, entitled, "Organisation Kriegsspiel". He demanded 40 000 German marks for the document but his superiors in Warsaw refused to pay that much believing that the information he possessed was actually German disinformation. Sosnowski entered into a secret deal with von Natzmer. Ritter von Nalecz cut the price by half and finally after which he sent all documents to Warsaw for at no charge.The Polish authorities still declined to take advantage of these documents.

It is widely recognized that until 1934, the In-3 office headed by Sosnowski, and its base at the Polish Embassy in Berlin, were the best among foreign branches of Polish intelligence, its activities costing around 2 million zlotys, an expensive venture indeed.

By the fall of 1933 the Abwehr obtained details of the Polish network of agents from Lieutenant Jozef Gryf-Czajkowski, a double agent who had previously held Sosnowski’s post in Berlin and from Maria Krusek, a German actress and one of Sosnowski's lovers, both of whom betrayed Sosnowski in their allegiance to the Abwehr.

On February 27, 1934, Sosnowski was arrested by the Gestapo during a party in an apartment at 36 Lützowufer Street. Within days, many people were arrested including Benita von Falkenhayn, Renate von Natzmer, and Irene von Jena. Günther Rudloff avoided arrest claiming that he provided useful intelligence information to the Abwehr only because of his liaison with Sosnowski. Only later did the Nazis discover the truth about Rudloff's activities, and he was sentenced to death. He committed suicide on July 7, 1941.

On February 16, 1935 von Falkenhayn and von Natzmer were sentenced to death and later executed by at Plötzensee prison by beheading. Sosnowski and von Jean were sentenced to life imprisonment.

Sosnowski was bereaved at the deaths of his mistresses. He was quoted in Time Magazine, in the August 16, 1936 issue: "I am haunted by the deaths of those women. Until I was released in an exchange of prisoners I had seen no human face for 14 months. My food was lowered to me by guards from a trap door. The tragic deaths of those two - my former associates - haunt me night & day and I can only attempt to gain peace through prayer for their souls"

According to heresay Benita von Falkenhayn wanted to marry Sosnowski and obtain a Polish passport, thus saving her life, but Adolf Hitler thwarted her attempt.

Sosnowski was released in April 1936 when he was exchanged for three German spies caught in Poland. However, Polish headquarters instead accused Sosnowski with fraud and high treason and put him under house arrest. They had always been suspicious of Sosnowski and of his great successes.

His trial began on March 29, 1938 in the Military District Court in Warsaw where he was charged with treason and for collaborating with Germany. Sosnowski denied all charges but on June 17, 1939 he was found guilty and sentenced to 15 years imprisonment as well as a fine of 200 000 zlotys. He was about to appeal the decision but the outbreak of World War II made it impossible .

After this point in time, It is difficult to determine the fate of Sosnowski. According to one report he was evacuated east from prison in early September 1939 and shot by the prison guards on September 16 or 17, near Brzesc nad Bugiem or Jaremcze.

Another report claims that Sosnowski was shot but survived only to be captured later by the NKVD. He was arrested on November 2, 1939 by order of Pavel Sudoplatov and transported to the Lubyanka prison

By the time the German-Soviet war

In the same year he allegedly was transferred to German-occupied Poland, where he cooperated with the communist People’s Army. It is rumoured that in September 1944 during the Warsaw Uprising

Ivan Serov maintained that Sosnowski was executed by the Home Army

source:

Wikipedia

Suggested Links:

"Love, Espionage and the Ax" (English, German, and Polish translations)

"Germany: Baroness Beheaded" Time Magazine, February 25, 1935

SPY WEEK Famous Polish Spies - Kazimierz Leski

Kazimierz Leski

Kazimierz Leski (June 21, 1912 - May 27, 2000) was a Polish engineer and co-designer of Polish submarines

(June 21, 1912 - May 27, 2000) was a Polish engineer and co-designer of Polish submarines ORP Sep, and ORP Orzel, as well as a fighter pilot, and officer of Home Army intelligence

ORP Sep, and ORP Orzel, as well as a fighter pilot, and officer of Home Army intelligence and Counter-Intelligence during World War II. His code name was Bradl.

and Counter-Intelligence during World War II. His code name was Bradl.

He traveled throughout German-occupied Europe on at least 25 missions disguised in the uniform of a Wehrmacht Major General.

After the war he was arrested and imprisoned by the communist authorities of the People's Republic of Poland and spent seven years on death row before being rehabilitated in 1956. Thereafter he resumed his career as an engineer.

Kazimierz Leski was born in Warsaw. His father, Major Juliusz Leski, had been an engineer and pioneer of Poland's arms industry after the Polish-Bolshevik War . However, following the May 1926 Coup d'Etat

. However, following the May 1926 Coup d'Etat , he fell from grace with the Polish authorities. but remained loyal to the government. Consequently, Kazimierz had to work as a railway worker in order to pay for his studies at the Wawelberg and Rotwand College in Warsaw. He also obtained work in a red at also got a simple job in the foundry of the Pocisk munitions works. He pursued intensive study of English, French, Russian and German in order to be able to study professional books skills that would prove invaluable later on.

, he fell from grace with the Polish authorities. but remained loyal to the government. Consequently, Kazimierz had to work as a railway worker in order to pay for his studies at the Wawelberg and Rotwand College in Warsaw. He also obtained work in a red at also got a simple job in the foundry of the Pocisk munitions works. He pursued intensive study of English, French, Russian and German in order to be able to study professional books skills that would prove invaluable later on.

Immediately after his graduation in 1936, he was offered a job at the Nederlandsche Vereenigde Scheepsbouw Bureaux design bureau (NVSB) in The Hague. The company was the leading design bureau in the Netherlands and worked on projects for all the major naval shipyards in the country.

Leski began work as a draughtsman and quickly learned the Dutch language. This allowed him to rise quickly through the ranks of the design bureau. But when Holland had won a contract for the construction of two modern Ozel class submarines for the Polish Navy, it significantly sped up Leski's success in the Dutch shipbuilding industry.

He enrolled at the Maritime Faculty of Delft University of Technology and began additional studies, after which he became one of the heads of the Submarine Division of the NVSB. He was responsible for the comparison of the projects with the supplied machinery. He also patented a new mounting for the ballast tank funnels for which he was promoted and went on to become an independent specialist. Soon afterwards Leski was appointed the head designer for the Orzel class submarines: the future ORP Orzełl and ORP Sep, as well as the deputy to the lead constructor Niemeier.

When the ship series were completed, he returned to Poland, where he enlisted in the Polish Army and graduated from the NCO Aviation School in Deblin .

.

War begins

When Poland was invaded by Germany in September 1939, Leski joined the Polish Air Force . But on September 17, 1939 during the Soviet invasion, his Lublin R-XIII F plane was shot down by the Soviets, and Leski was badly injured. He was taken prisoner of war by Soviet soldiers but managed to escape and reach Lwów. From there he crossed the new Soviet-German "border of peace" and in October 1939 relocated to Warsaw, where he joined an underground organization, Muszkieterowie ("The Musketeers").

. But on September 17, 1939 during the Soviet invasion, his Lublin R-XIII F plane was shot down by the Soviets, and Leski was badly injured. He was taken prisoner of war by Soviet soldiers but managed to escape and reach Lwów. From there he crossed the new Soviet-German "border of peace" and in October 1939 relocated to Warsaw, where he joined an underground organization, Muszkieterowie ("The Musketeers").

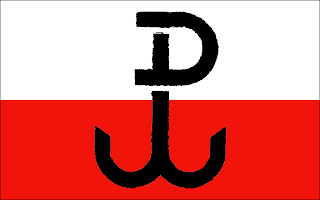

The group was an en cadre military organization whose primary focus was on intelligence. They were later integrated into the Home Army (Armia Krajowa ), Leski –still suffering from wounds received in September 1939, was not fit for front-line service in the Forest Units and thus became a leading intelligence officer with the Musketeers and subsequently with the Home Army.

), Leski –still suffering from wounds received in September 1939, was not fit for front-line service in the Forest Units and thus became a leading intelligence officer with the Musketeers and subsequently with the Home Army.

Among his list of achievements, was the collection of a complete list of German military units, their insignia, numbers and dispositions. Leski and his cell also prepared detailed reports on the logistics and transport of German units bound for the Eastern Front, as well as the state of bridges, railways and roads throughout German-occupied Europe. In addition, they also developed a sophisticated communications network spanning German-occupied Europe from Poland all the way to Portugal, France and the Polish Government in Exile in the Great Britain.

Disguises

In 1941 Leski embarked on his first mission as courier to France. He posed as a Lieutenant of the Wehrmacht but decided to promote himself to the rank of "Generalmajor"for all other trips so that he could travel first class. Because of his wounds it was out of the question to travel in crowded, third-class railway cars.

Travelling under the name General Julius von Halmann, Leski managed to cross Europe many times with without his true identity being revealed. His disguise, fluency in several languages and his flawlessly forged documents gave him the privilege of witnessing many key events that he would otherwise not be privy to. One such event was during his 1942 visit to the Atlantic Wall construction site. It was made possible only because he managed to persuade one of the passengers in his car that his superiors might be interested to build a similar line of fortifications in the Ukraine. Another event was during his visit to the field staff of Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt.In addition to his service in intelligence and counter-intelligence, he took command over a cell whose activities were primarily focused on smuggling information and people in and out of German prisons in occupied Poland, notably the infamous Pawiak prison .

.

Warsaw Uprising

When the Warsaw Uprising began in August 1944, Kazimierz Leski was not commissioned. He fought in an infantry battalion which he formed, Milosz, and became Commander of its first company, Bradl. The unit fought with distinction in the area of Triple Cross Square in the Warsaw City Center. Leski was promoted to captain and decorated with several medals for his leadership and valor including the Silver Virtuti Militari, the Gold and Silver Crosses of Merit with Swords, and three Crosses of Valor.

began in August 1944, Kazimierz Leski was not commissioned. He fought in an infantry battalion which he formed, Milosz, and became Commander of its first company, Bradl. The unit fought with distinction in the area of Triple Cross Square in the Warsaw City Center. Leski was promoted to captain and decorated with several medals for his leadership and valor including the Silver Virtuti Militari, the Gold and Silver Crosses of Merit with Swords, and three Crosses of Valor.

After Warsaw capitulated Leski managed to escape from a column of prisoners and pretending to be a civilian returned to the Polish Underground. He became a commander of the Home Army Western Area and later Chief of the Armed Forces Delegation for Poland.

Communist prison

After the communist takeover of Poland Leski's underground network disbanded and he relocated to Gdansk. He became a member of the Wolnosc i Niezawislosc anti-communist resistance, under using the the false name "Leon Juchniewicz" he became the first managing director of the demolished Gdańsk Shipyards. Among his tasks was the reconstruction of the shipyard which had been destroyed by Allied air raids and by withdrawing Germans. In August 1945 the Polish communists presented him with the highest civil award, but later on the very same day was arrested by the Polish secret police. They had discovered his true identity.

He was charged with attempting to overthrow the communist regime and was sentenced to 12 years in prison. The sentence was later changed to six years. In 1951 however he was not released but charged with collaborating with German forces, and he remained in prison for several years more. He was subjected to solitary confinement and brutal torture.

Finally after the deaths of Stalin in 1953 and Bierut in 1956, Kazimierz Leski was released from prison, and rehabilitated soon afterwards. Despite that, he was unable to find a job, as the new communist authorities of Poland regarded former soldiers of the Home Army with suspicion. He managed to obtain employment as a clerk in the PWT publishing house and had to give up his ambition to work in the shipbuilding industry.

in 1953 and Bierut in 1956, Kazimierz Leski was released from prison, and rehabilitated soon afterwards. Despite that, he was unable to find a job, as the new communist authorities of Poland regarded former soldiers of the Home Army with suspicion. He managed to obtain employment as a clerk in the PWT publishing house and had to give up his ambition to work in the shipbuilding industry.

Finally he became a member of the Polish Academy of Sciences and was awarded a Doctorate. For political reasons he was prevented from earning the rank of Professor for his work on computer analysis of natural language codes. Nevertheless, he continued his scientific career, publishing 7 books and more than 150 other works. He also patented a number of inventions.

and was awarded a Doctorate. For political reasons he was prevented from earning the rank of Professor for his work on computer analysis of natural language codes. Nevertheless, he continued his scientific career, publishing 7 books and more than 150 other works. He also patented a number of inventions.

In 1989 after the victory of Solidarity and fall of the communist regime in Poland Leski published his memoirs, which became an immediate best-seller. For the book he received a number of prizes, among them the Polish PEN Club Prize and the Polish Writers' Society in Exile Award.

and fall of the communist regime in Poland Leski published his memoirs, which became an immediate best-seller. For the book he received a number of prizes, among them the Polish PEN Club Prize and the Polish Writers' Society in Exile Award.

In 1995 the Yad Vashem Institute honored him with the title " Righteous Among the Nations" for saving Jews during the Second World War.

He died on May 27, 2000 and was interred with military honors at Warsaw's Powazki Cemetery.

source: Wikipedia

Suggested Links:

Polish Navy

Home Army History

The Polish Righteous

Editors Note: FYI: The images of medals posted here may or may not be the exact version which was awarded to the recipient. There are several classes for each medal depending on various factors such as type of military (or civilian) service, rank of officer (or soldier), class of award, year in which it was awarded, etc The lack of sufficient information on the web (or omission) has compounded the difficulty in selecting the correct class of medal. I apologize for any inaccuracies.

Kazimierz Leski

He traveled throughout German-occupied Europe on at least 25 missions disguised in the uniform of a Wehrmacht Major General.

After the war he was arrested and imprisoned by the communist authorities of the People's Republic of Poland and spent seven years on death row before being rehabilitated in 1956. Thereafter he resumed his career as an engineer.

Kazimierz Leski was born in Warsaw. His father, Major Juliusz Leski, had been an engineer and pioneer of Poland's arms industry after the Polish-Bolshevik War

Immediately after his graduation in 1936, he was offered a job at the Nederlandsche Vereenigde Scheepsbouw Bureaux design bureau (NVSB) in The Hague. The company was the leading design bureau in the Netherlands and worked on projects for all the major naval shipyards in the country.

Leski began work as a draughtsman and quickly learned the Dutch language. This allowed him to rise quickly through the ranks of the design bureau. But when Holland had won a contract for the construction of two modern Ozel class submarines for the Polish Navy, it significantly sped up Leski's success in the Dutch shipbuilding industry.

He enrolled at the Maritime Faculty of Delft University of Technology and began additional studies, after which he became one of the heads of the Submarine Division of the NVSB. He was responsible for the comparison of the projects with the supplied machinery. He also patented a new mounting for the ballast tank funnels for which he was promoted and went on to become an independent specialist. Soon afterwards Leski was appointed the head designer for the Orzel class submarines: the future ORP Orzełl and ORP Sep, as well as the deputy to the lead constructor Niemeier.

|

| Orzel class Polish Submarine World War II |

When the ship series were completed, he returned to Poland, where he enlisted in the Polish Army and graduated from the NCO Aviation School in Deblin

War begins

When Poland was invaded by Germany in September 1939, Leski joined the Polish Air Force

|

| Fleet of Lublin R-XIII F plane World War II |

The group was an en cadre military organization whose primary focus was on intelligence. They were later integrated into the Home Army (Armia Krajowa

Among his list of achievements, was the collection of a complete list of German military units, their insignia, numbers and dispositions. Leski and his cell also prepared detailed reports on the logistics and transport of German units bound for the Eastern Front, as well as the state of bridges, railways and roads throughout German-occupied Europe. In addition, they also developed a sophisticated communications network spanning German-occupied Europe from Poland all the way to Portugal, France and the Polish Government in Exile in the Great Britain.

Disguises

In 1941 Leski embarked on his first mission as courier to France. He posed as a Lieutenant of the Wehrmacht but decided to promote himself to the rank of "Generalmajor"for all other trips so that he could travel first class. Because of his wounds it was out of the question to travel in crowded, third-class railway cars.

Travelling under the name General Julius von Halmann, Leski managed to cross Europe many times with without his true identity being revealed. His disguise, fluency in several languages and his flawlessly forged documents gave him the privilege of witnessing many key events that he would otherwise not be privy to. One such event was during his 1942 visit to the Atlantic Wall construction site. It was made possible only because he managed to persuade one of the passengers in his car that his superiors might be interested to build a similar line of fortifications in the Ukraine. Another event was during his visit to the field staff of Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt.In addition to his service in intelligence and counter-intelligence, he took command over a cell whose activities were primarily focused on smuggling information and people in and out of German prisons in occupied Poland, notably the infamous Pawiak prison

Warsaw Uprising

When the Warsaw Uprising

After Warsaw capitulated Leski managed to escape from a column of prisoners and pretending to be a civilian returned to the Polish Underground. He became a commander of the Home Army Western Area and later Chief of the Armed Forces Delegation for Poland.

Communist prison

After the communist takeover of Poland Leski's underground network disbanded and he relocated to Gdansk. He became a member of the Wolnosc i Niezawislosc anti-communist resistance, under using the the false name "Leon Juchniewicz" he became the first managing director of the demolished Gdańsk Shipyards. Among his tasks was the reconstruction of the shipyard which had been destroyed by Allied air raids and by withdrawing Germans. In August 1945 the Polish communists presented him with the highest civil award, but later on the very same day was arrested by the Polish secret police. They had discovered his true identity.

He was charged with attempting to overthrow the communist regime and was sentenced to 12 years in prison. The sentence was later changed to six years. In 1951 however he was not released but charged with collaborating with German forces, and he remained in prison for several years more. He was subjected to solitary confinement and brutal torture.

Finally after the deaths of Stalin

Finally he became a member of the Polish Academy of Sciences

|

| Polish Academy of Sciences |

In 1989 after the victory of Solidarity

In 1995 the Yad Vashem Institute honored him with the title " Righteous Among the Nations" for saving Jews during the Second World War.

He died on May 27, 2000 and was interred with military honors at Warsaw's Powazki Cemetery.

|

| Righteous Among Nations |

|

| Silver Cross Virtuti Militari |

|

| Gold Cross of Merit with Swords |

|

| Silver Cross of Merit with Swords |

|

| Cross of Valor |

source: Wikipedia

Suggested Links:

Polish Navy

Home Army History

The Polish Righteous

Editors Note: FYI: The images of medals posted here may or may not be the exact version which was awarded to the recipient. There are several classes for each medal depending on various factors such as type of military (or civilian) service, rank of officer (or soldier), class of award, year in which it was awarded, etc The lack of sufficient information on the web (or omission) has compounded the difficulty in selecting the correct class of medal. I apologize for any inaccuracies.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)